What is the context in which COP30 fits

La COP30, hosted by Belém, in the heart of the Brazilian Amazon, arrived in a Crucial moment for global climate diplomacy.

Choose the Amazonia As a venue, it was not a random gesture: it means taking international dialogue exactly where the climate crisis Show more clearly his urgency, in forests that absorb carbon, in vulnerable territories, in communities committed daily to the protection of ecosystems.

A Ten years from the signature of theParis Agreement, this COP had been presented as the 'COP of truth', because it called on countries to demonstrate if the commitments made were truly credible, and the 'COP of implementation', because it should have marked the transition from promises to concrete implementation plans.

After years of negotiations and formal commitments, theglobal expectation was clear: to transform promises into concrete actions, accelerate decarbonization and create a credible path to keep the 1.5°C goal still “within reach”.

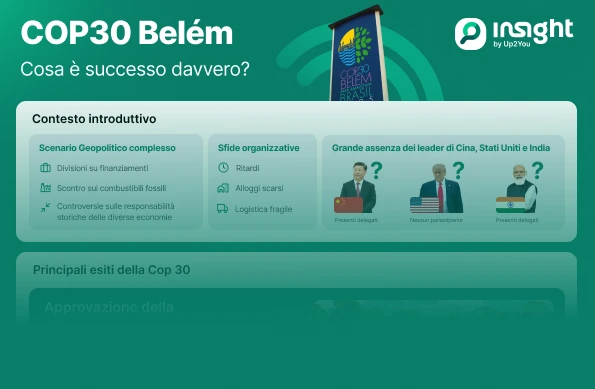

Despite the initial enthusiasm, COP30 took place in a complex geopolitical context. Negotiations quickly brought to light significant fractures, including:

- differences over the amount, management and source of climate finance;

- distances on the role of fossil fuels in the ecological transition;

- controversies related to the historical responsibilities of different economies.

Countries with developed economies, emerging nations and countries with economies strongly based on oil extraction, have arrived in Belém with profoundly different expectations, priorities and internal pressures.

The discussions about how Share fairly the weight of the ecological transition, and on whom it should contribute financially to accelerate it, they slowed down and inhibited the negotiation process.

The result was a negotiation that emerged in a Climate of constant tension, with delegations called to find compromises (downward) at a time when time for action is rapidly running out.

What made the picture even more complex were the logistical difficulties.

COP30 had to face transport delays, lack of housing and organizational unforeseen events (not least, a fire) that they created uneasiness for many delegations. Small signs, but which have contributed to a general climate of uncertainty.

On the political level, however, it was mainly the Great absences: the leaders of China, the United States and India, the three largest economies and main global emitters, did not attend the leaders' summit, and no US representative or coalition attended the COP. La Lack of presence of the USA, in particular, had a significant symbolic impact: at a time when the transition requires a strong response, the absence of Washington has left a vacuum that is difficult to ignore.

Click the button in the box on the side and download the free infographic that shows the outcomes and unresolved issues of COP30

What are the main outcomes of COP30

The 'Global Mutiirão Decision': a container that holds the negotiating threads together

The main result of COP30 is the approval of Global Decision Mutiron, an umbrella decision that brings together different negotiating lines in a single framework: finance, transparency, ambition, adaptation and implementation capacity.

The stated objective was to give consistency with the negotiation, preventing the various working groups from operating on separate and non-communicating tracks.

Despite this integrated vision, the final document has obvious limitations: It does not contain any mandatory roadmap for the phase-out of fossil fuels (not even mentioned in the negotiations), the issue at the center of the global climate emergency.

The result is a structured decision, useful as a frame of reference, but still devoid of a binding and concrete direction to address the climate crisis.

Adapting to climate change: funding tripled

One of the most significant results of COP30 concerns theadjustment, which has emerged as a top priority for the Brazilian presidency.

The increasing exposure to extreme weather events, heat waves, torrential rains, increasingly high economic losses, has made evident the need to strengthen the protection systems of vulnerable communities and territories.

In this context, countries have agreed on the need to Triple adaptation funding by 2035, a significant political commitment that marks a change of pace compared to previous years. However, the final text does not yet define key elements such as the baseline from which to start or the reference year on which to calculate fund growth: a detail that is not secondary, which will make The measurement of progress is complex until it's clarified.

1.5°C target: overshoot is likely

Another important passage of COP30 concerns the more realistic tone assumed with respect to the objective of containing global warming within 1.5°C.

For the first time, a UN negotiating text openly recognizes that a 'overshoot' of 1.5°C is very likely.

This admission does not represent a waiver, but an invitation to limit as much as possible the duration and magnitude of the overcoming, reinforcing the urgency of climate action.

The document explicitly calls on countries to:

- accelerate the implementation of its NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions), national climate plans that every country that signs the Paris Agreement must submit;

- realign public and private investments to the 1.5°C trajectory;

- improve the coherence between national plans, sectoral policies and financial flows.

It is an important step because connects the scientific dimension to the economic dimension, Indicating that the battle for 1.5°C is being played out a lot on reduction of emissions as to the capacity of States to guide investments and policies.

A New Mechanism for the Just Transition

Among the decisions considered most positive at COP30, the approval of a Just Transition Work Programme (JTWP), a mechanism designed to support a fair and inclusive transition.

This program formally recognizes the role of workers, vulnerable communities and indigenous peoples, integrating their rights into the process of economic transformation and climate policies.

Alongside the program, the proposal of Belem Action Mechanism (BAM), conceived as a possible global architecture to move from simple dialogue on “just transition” to coordinated and measurable action. The BAM aims to:

- tidying up today's fragmented initiatives on the just transition;

- improve how countries plan, implement and monitor transition policies;

- channel technical and financial support (not debt-based) to the most exposed countries and communities.

The proposal was strongly pushed by civil society and trade unions, and obtained the support of the G77 + China group, which represents more than80% of the world's population, while several developed countries have shown resistance, fearing overlaps with existing tools.

Overall, the Just Transition package, between JTWP and BAM, represents one of A few clear steps forward towards a transition that leaves no one behind, although it still remains partly to be defined operationally.

What are the unresolved issues of COP30

No binding agreement on the phase-out of fossil fuels

Despite expectations on the eve, COP30 failed to produce a binding agreement on the phase-out of coal, oil and gas. The theme, central to the credibility and coherence of global climate action, has remained the The most divisive point in the negotiation.

The Brazilian presidency had proposed the adoption of a international roadmap capable of guiding the progressive reduction of fossil fuels, but the confrontation quickly ran aground.

Le Petrostate resistors, in particular Saudi Arabia, Russia and other major oil exporters, have prevented the inclusion of any explicit reference to fossil fuels in the final text. For these countries, a formal commitment to reduce oil and gas production represents a real 'red line', which is difficult to overcome in multilateral negotiations.

The result of the Global Mutiirão, the summary decision approved in Belém, It does not contain any roadmap nor does it call for a phase-out. An obvious lack, especially considering that climate science identifies precisely fossil fuels as the fulcrum of the crisis.

A missing roadmap on deforestation

The other big one missing in the final text is a binding roadmap on deforestation. A paradox considering that COP30 took place in Belém, in the heart of the Amazon, where the protection of forests represents one of the most immediate levers to contain global warming.

The negotiations failed to converge on a shared agenda to end the loss of tropical forests. The positions of the producer countries, the differences on financing mechanisms and the fear of constraints that are too stringent have prevented from entering clear and verifiable objectives.

The topic was therefore left out of the Global Mutiirão, postponed to future discussions and parallel paths.

The alternative path: a voluntary roadmap outside the UN process

Faced with the stalemate over fossil fuels and deforestation, the presidency of COP30 chose an alternative path so as not to let the topic fall. President André Corrêa do Lago has in fact announced the start of a voluntary roadmap, developed outside of formal United Nations negotiations.

This initiative, which will be presented in 2026 in a dedicated international conference, aims to build a coalition of countries willing to commit more quickly and with greater ambition to:

- energy transition and reduction of the use of fossil fuels,

- forest protection and the fight against deforestation.

It is therefore a parallel path, open to those who want to join on a voluntary basis, with the aim of keeping alive the political momentum created by Brazil and to advance issues that have not found space in the final text of the COP.

What does COP 30 leave behind: implications and critical issues

COP30 marked some important steps forward, but it also highlighted significant limitations in global ambition.

The lack of inclusion of key elements such as a roadmap on fossil fuels, a central theme for mitigation, shows how much Multilateral consensus remains fragile whenever strategic interests related to oil and gas are touched upon.

For many observers, this represents the real Weak spot of the Belém agreement: a compromise that reflects more current geopolitical balances than scientific urgency.

Alongside these critical issues, however, COP30 reaffirmed a fundamental need: transform political commitments into concrete implementation, equipped with transparency, monitoring and adequate resources. Without operational tools and reliable funding, even the most advanced decisions risk remaining only on paper.

For those who work in sustainability and ESG, this context brings with it three direct implications. Let's see what they are.

- Right transition: with a new dedicated program at UN level, it becomes essential to integrate social considerations into corporate climate strategies, evaluating impacts on communities and workers.

- Adaptation: the commitment to triple funding by 2035 and the introduction of GGA indicators will gradually lead to more stringent requirements for climate risk management and reporting.

- Monitor how the adaptation finance baseline will be defined and how the rules will evolve: access to funds, operational priorities and opportunities for resilience projects in the most exposed countries and sectors will depend on these choices.

So let's understand how COP30 has not closed all open issues: the very limits of the COP have laid the foundations for work that in the coming years will require greater implementation, consistency and ability to translate political commitments into measurable results. For businesses, this means preparing for a phase in whichAligning with climate objectives will no longer be an option, but a necessary condition to operate, and to do so in a credible and responsible way, in order to propose a real corporate sustainability.

What to expect after COP30

The COP30 left many on the table Open issues And just as many promises to be realized.

Next year will therefore be decisive in understanding whether the commitments made in Belém will be able to transform into real actions, especially in view of the COP31 in Turkey, where negotiations must necessarily enter the operational phase.

One of the most anticipated points concerns the definition of Volunteer roadmap on fossil fuels and deforestation. Even if they were not included in the official text of COP30, these parallel paths could become an important test: COP31 will have to clarify who will join, what commitments will be made and how progress will be monitored.

Their credibility will depend on countries' ability to translate them into concrete measures, with clear and verifiable timelines.

Another crucial element will be the strengthening of the monitoring of the 59 indicators of the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), agreed right in Belém. These indicators represent the first common basis for evaluating global progress on adaptation, but their effectiveness will depend on the real commitment of countries to collect data, make them comparable and above all transform them into targeted policies and investments.

2026 will be the year in which the difference between ambitions on paper and implementation skills.

The trajectory to The 1.5 °C target it will finally exert ever increasing pressure on the international system. With the formal recognition that an overshoot is likely, there is a growing urgency to intervene on three fronts:

- mobilization of climate finance,

- Increase in transparency on national policies,

- Definition of stricter methods to measure progress towards reducing emissions.

The global community now asks for clarity, consistency and accountability. The success of COP31 will largely depend on the ability of States to present themselves with updated plans, realigned investments and a real will to accelerate. For companies and sustainability professionals, this means preparing for a context in which monitoring, reporting and integrating climate objectives into business models will become increasingly central requirements.